Features

In this chapter, we explain BraneScript from a user experience perspective. We go over the main design choices and language concepts it features to understand what the rest of this appendix is working towards.

If you are already familiar with BraneScript as a user and want to learn how to parse it, refer to the Formal grammar chapter; if you are instead interesting in compiling the resulting AST to the Workflow Intermediate Representation (WIR), refer to the subsequent chapters instead.

BraneScript: A scripting-like language

Primarily, BraneScript is designed to emulate a scripting-like language for defining workflows. As such, it is not approximating a graph structure, as workflows are typically represented, but instead defines a series of statements and expressions that can arbitrarily call external tasks. This means the language is very similar in usage as Lua or Python, "unfolding" to a workflow more than directly encoding it. Listing 1 shows an example BraneScript snippet.

// Import a package that defines external tasks

import hello_world;

// Print some text running it on a particular location!

#[on("site_1")]

{

println("A message has come in:");

println(hello_world());

}

// Print a lot more text running it on another location!

#[on("site_2")]

{

println("Multiple messages coming in!:");

for (let i := 0; i < 10; i := i + 1) {

print("Message "); print(i); print(": ");

println(hello_world());

}

}

Listing 1: Example BraneScript snippet showing how the language looks using a typical "Hello, world!" example.

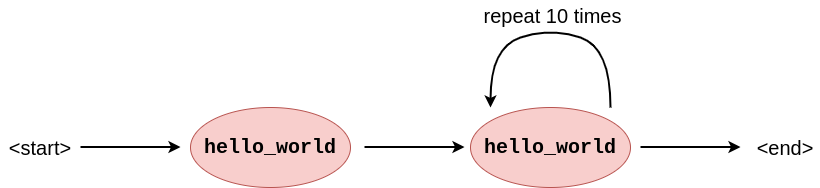

At compile time, the statements are analysed by the compiler to derive the intended workflow graph. Such a graph matching Listing 1 can be found in Figure 1.

Figure 1: Workflow graph that can be extracted from Listing 1. It shows the initial task execution and then the repeated execution of the same function. In practise, this loop might be unrolled for simpler analysis, but this cannot always be done (e.g., conditional loops).

Main concepts

BraneScript leans on well-established concepts from other programming languages.

First, a BraneScript program is defined as a series of statements. These are the smallest units of coherent programs. Statements typically indicate control flow between expressions (see below), where particular constructs can be used for particular types of flow (e.g., if-statements, for-loops, while-loops, parallel-statements, etc). Like most scripting languages, they needn't be nested in a function (see below).

Actual work is performed in expressions, which can be thought of as imperative formulas creating, transforming and consuming values. Aside from literal values (booleans, integers, real numbers, strings), BraneScript also supports arrays of values (i.e., dynamically-sized containers of multiple of the same values) and classes (i.e., statically-sized containers of different values). Operations supported in expressions are logical operations (conjunction, disjunction), arithmetic operations (addition, subtraction, multiplication, division, modulo) and comparison operators. Operations like array indexing or function calls are also supported.

BraneScript also has a concept of variables, which can remember values across statements. Essentially, these are named segments of memory that can be assigned values that can later be read.

Functions can be used to make the codebase more efficient, or implement specific programming paradigms (such as recursion). Formally, functions can be thought of as "custom operations" in expressions. They might take in a value, define how to process that value and then potentially return a (new) one. Not all functions do this, though, and instead may produce side-effects by calling builtin- or package methods.

Note that classes can also be associated with functions to define class methods.

Finally, specific to BraneScript, external functions are imported as packages and treated like normal function within the scripting language. However, instead of executing BraneScript statements, these functions execute a workflow task dynamically on Brane infrastructure. Their result is translated back to BraneScript concepts.

Statements

This section lists the specific statements supported by BraneScript.

Expression statements

println("Hello, world!");

42 + 42;

55 + add(33, 44);

Expression statements represent the straightforward execution of a particular expression. The result of the expression is not stored (see below), and so it is typically used for function calls which do not return a value, or if we're not interested in the returned value.

(Let) Assignments

// Example assignment to new variables

let value := 42;

// Example assignment to existing variables

value := 42 * 2;

Let assignments are like expression statements, except that the value computed by the expression is stored in a variable.

There are two versions of this syntax: first, there is the let assignment, which can be used to declare a variable and immediately assign it a particular value. Then, once the variable has been declared, its value can be updated using a normal assignment.

If-statements

// This assigns either 42 or 82, depending on the value of `foo`

let foo := true;

let bar := null;

if (foo) {

bar := 42;

} else {

bar := 84;

}

// The variation that only defines a true-branch

let foo := true;

let bar := null;

if (foo) {

bar := 42;

}

If-statements represent a conditional divergence in control flow. It analyses a given expression that evaluates to a boolean, and executes one of two branches of statements: the top one if the value is true, or the bottom one if it's false.

A variation of this statement exists where the second branch may be omitted if it contains no statements.

While-loops

let counter := 0;

while (counter < 10) {

println("Hello, world!");

counter := counter + 1;

}

Sometimes, a series of statements needs to be repeated a conditional number of times. In these cases, a while-loop can be used; it repeats a series of statements as long as the given boolean expression evaluates to true.

For-loops

for (let i := 0; i < 10; i := i + 1) {

println("Hello, world!");

}

As syntax sugar for a while-loop, a for-loop also repeats a series of statements until a particular condition is reached. It is tailored more for iterations that are repeated a particular number of items instead of an arbitrary condition.

The syntax of the for-loop is as follows. The input to the loop is separated into three parts using semicolons: the first is executed before the loop; the second is used as the while-loop's condition; and the last part is executed at the end of every loop.

Note that, while the styling suggests a C-like syntax, it is not as freeform as that. Instead, only the name of the variable (i, in the example), the condition (i < 10) and the increment-expression (i + 1) can be changed.

Parallel statements

// Execute stuff in parallel!

parallel [{

println("Hello, world! 1");

}, {

println("Hello, world! 2");

}];

// Alternative form to return a value (and showing multiple branches are possible)

let result := parallel [all] [{

return 42;

}, {

return 84;

}, {

return 126;

}];

The parallel-statement is slightly more unique to BraneScript, and denotes that two series of statements can be executed in parallel. This is mostly useful when either contains external function calls, but in practise also launches the BraneScript statements concurrently.

There are two forms of the statement. In the first, work is just executed in parallel. In the second, a value may be returned from the branches (using a return-statement) that is aggregated somehow and placed in the variable preceding the statement. How the variables are aggregated is denoted by the merge strategy ([all] in the example).

Block statements

// We can nest statements in a block arbitrarily to play with scoping rules

let foo := 42;

println(foo); // 42

{

// Shadowed!

let foo := 84;

println(foo); // 84

}

println(foo); // 42

Typically, blocks of statements are used in function declarations, if-statements or other constructs. Essentially, they just group statements together visually. However, importantly, blocks also directly define scopes, i.e., they specify which variables are visible and thus usable for the programmer. When using a block as a separate statement, it is used to introduce an additional scope to shadow variables or free values early.

Function declarations

// A function without arguments

func hello_world() {

println("Hello, world!");

}

// A function _with_ arguments!

func add(lhs, rhs) {

return lhs + rhs;

}

Functions can be used to group statements under a particular name, which can then later be called. The function declarations define which statements are executed, and which arguments the function has as input. Syntactically, these are represented as variables scoped to the function and populated when a call is performed.

To return a value from the function to the calling scope, use return-statements.

Return statements

// Returns '42' from the workflow

return 42;

// Only interrupts the control flow, returns nothing

return;

To return values from functions, a return-statement may be used. When executed, it immediately interrupts the current body (either from a function or the main script body), and goes back to where that was called. When given with a value, that value subsequently gets set as the value of the function call. When used at the toplevel of the script, this means that returns terminate the whole script and potentially return a value back to the user. In parallel stements, they are used to terminate branches and return values for aggregation.

Import statements

// Import the latest available version of a package

import hello_world;

// Or a specific version

import hello_world[1.0.0];

Unique to BraneScript are import-statements, which are used to bring the external functions of packages into scope. They can either be given without version number, in which case the latest version is used, or with, in which case the given version is used.

Note that imports are always relative to the execution context, not the compile context.

Class declarations

// A class is a statically-sized, heterogenous container of multiple values

class Test {

value1: int;

value2: string;

// ...with functions that can act on it!

func print(self) {

print(self.value1);

print(" and '");

print(self.value2);

println("'");

}

}

Oftentimes, it is practical to group multiple values together. A BraneScript class is one way of doing so. Unlike arrays, classes can contain values of different types; but to do so, first they have to be statically defined so that the execution engine knows the shape of the class and how to access its contents.

To support OOP-like programming paradigms, BraneScript classes can also be annotated methods. These are functions that act on a particular instance of a class, and come accompanied with convenient syntax for using them. Note, however, that BraneScript misses a few features for using full OOP; for example, there is no way to define object inheritance.

Syntactically, the class is defined as a special kind of block that lists its contents (fields) as name/type pairs. A function can be given, which always takes self as first parameter, to define a method. Note that associated functions (i.e., functions without self) are not supported.

Attributes

#[on("foo")]

#[tag("amy.bar")]

#[something_else]

#![inner_annotation]

As a final BraneScript statement, attributes (sometimes called annotations) can be used to provide some additional metadata to the compiler. While syntactically, any identifier can be used, only a few are recognized by the compiler, having their own syntax for arguments.

Attributes in the form of #[...] always annotate the first non-attribute statement succeeding it. If this statement has nested statements (e.g., a block, if-statement, etc), then the attribute is propagated to all the nested statements as well. For example:

#[attribute]

{

// The if-statement is annotated with `attribute`

if (true) {

// And this expression-statement has `attribute` too

println("Hello, world!");

}

}

As an alternative syntax, the #![...]-form (not the exclaimation mark !) annotates every statement in the parent block. To illustrate:

// Same effect as the snippet above!

{

#![annotate]

// The if-statement is annotated with `attribute`

if (true) {

// And this expression-statement has `attribute` too

println("Hello, world!");

}

}

This latter form can be used to annotate an entire BraneScript file (e.g., wf-tag; see below).

The following attributes are currently recognized by the compiler:

on(<locs...>)ORloc(<locs...>)ORlocation(<locs...>): Explicitly states domains in a Brane instance where a particular external call must be executed. This can be used to implement Trusted Third-Parties, for example.tag(<tags...>)ORmetadata(<tags...>): Adds an arbitrary piece of metadata (a string) to external calls, which may be used by policy to learn information non-derivable from the call itself. An example of this would be GDPR-like purpose tags. Note that the tags must be given as<owner>.<tag>, where the owner is the domain or entity responsible for defining it.wf-tag(<tags...>)ORworkflow-tag(<tags...>)ORwf-metadata(<tags...>)ORworkflow-metadata(<tags...>): Adds an arbitrary piece of metadata (a string) to the workflow as a whole, which may be used by policy to learn information non-derivable from the call itself. An example of this would be GDPR-like purpose tags. Note that the tags must be given as<owner>.<tag>, where the owner is the domain or entity responsible for defining it.

Expressions

This section lists the particular operators and other constructs that can be used in BraneScript expressions.

Note that expressions are typically defined recursively, meaning that arbitrarily complex expressions can be built by nesting them (e.g., 42 + 42 - 42 nests the addition as a child of the subtraction).

Literals

42

"Amy"

84.0

true

1.0.0

null

The simplest expression possible is a literal, which evaluates to the value written down. For every primitive data type, there is an associated literal; these are booleans, integers, real numbers, strings, version triplets and null.

Variable access

foo

Instead of providing a literal value, a variable can also be referenced. In that case, it evaluates to the value that was assigned to it most recently, of the type associated with the variable (see the rules about typing).

Operators

42 + 42

4 * 8

"Hello, " + "world!"

!true

-42

-82.0

42 % 4 - 3

Operators can be used to manipulate the results of other expressions. Available operators can be separated into roughly two classes: unary operators, which take only a single expression; and binary operators, which manipulate two expressions, usually aggregating them somehow.

Note that operators are subject to precedence (i.e., which operator should be considered first) and associativity (i.e., in which order are the operators considered when all of the same type). These are discussed in the formal grammar chapter.

The following operators are available in BraneScript:

- Logical operators

- Negation (

!<bool expr>): "Flips" the boolean value (e.g., true becomes false and false becomes true). - Conjunction (

<bool expr> && <bool expr>): Takes the logical conjunction of the two values (i.e., returns true iff both expressions are true). - Disjunction (

<bool expr> || <bool expr>): Takes the logical disjunction of the two values (i.e., returns true iff at least one of both expressions is true).

- Negation (

- Arithmetic operators

- Addition (

<int expr> + <int exprOR<real expr> + <real expr>OR<str expr> + <str expr>): Adds two numerical values, or concatenates two strings. - Subtraction (

<int expr> - <int expr>OR<real expr> - <real expr>): Subtracts the second value from the first. - Multiplication (

<int expr> * <int expr>OR<real expr> * <real expr>): Multiplies two numerical values. - Division (

<int expr> / <int expr>OR<real expr> / <real expr>): Divides the first value by the second. The first case defines integer division, which is like normal division except that the answer is always rounded down to the nearest integer. - Modulo (

<int expr> % <int expr>): Returns the remainder after integer dividing the first value by the second.

- Addition (

- Comparison operators

- Equality (

<expr> == <expr>): Evaluates to true if the two values are the same (including of the same type), or false otherwise. - Inequality (

<expr> != <expr>): Evaluates to true if the two values are not the same (happens when they don't share the same type), or false otherwise. - Less than (

<int expr> < <int expr>OR<real expr> < <real expr>): Evaluates to true if the first value is strictly lower than the second value. - Less than or equal (

<int expr> <= <int expr>OR<real expr> <= <real expr>): Evaluates to true if the first value is lower than or equal to the second value. - Greater than (

<int expr> > <int expr>OR<real expr> > <real expr>): Evaluates to true if the first value is strictly higher than the second value. - Greater than or equal (

<int expr> >= <int expr>OR<real expr> >= <real expr>): Evaluates to true if the first value is higher than or equal to the second value.

- Equality (

Function calls

println("Hello, world!")

add(42, foo)

magic_number()

add(magic_number(), 42 / 2)

After a function has been defined, it can be called as an expression. It can be given arguments if the declarations declares them, which are nested expressions that should evaluate to the type required by that function.

After the call completes, the function call evaluates to the value returned by the function. Functions returning nothing (i.e., Void) will always cause type errors when their value is used, so only use that as a "terminating" expression (i.e., one that is not nested in another expression and who's value is not used).

Note that calls to external functions (i.e., those imported) use the exact same syntax as regular function calls.

Arrays

[]

[1, 2, 3, 4]

[magic_numer(), 42 + 4, 88]

As an alternative to classes, arrays are part of BraneScript as ad-hoc containers for values of a shared type. In particular, and array can be thought of as a continious block of data of variable length.

Arrays can be constructed using Python-like syntax, after which they will evaluate to an array of the type of its elements. As it is an expression, it can be stored in variables and used for later.

Array indexing

foo[0]

[1, 2, 3][5]

generates_array()[4 - bar]

To access the contents of an array instead of the array as a whole, an index expression can be used. This takes in an expression evaluating to an array first, and then some (zero-indexed!) index into that array. The index expression as a whole evaluates to the selected element.

Note that using an index that is the same or higher than the length of the array will cause runtime errors.

Class instantiation

new Test { value1 := 42, value2 := "Hello, world!" };

new Jedi {

name := "Obi-Wan Kenobi",

is_master := true,

lightsaber_colour := "blue"

}

new Data { name := "test" }

After a class has been declared, it can be instantiated, meaning that we create the container with appropriate values. The syntax used writes the fields as if they were assignments, taking the name before the := and an expression evaluating to that field's type after it.

Projection

test.value1

jedi.is_master

big_instance.small_instance.value

Once a class has been instantiated, its individual values may be accessed using projection. This selects a particular field in the given class instance, and evaluates to the most recently assigned value to that field.

The syntax is first an expression evaluating to an instance (including other projections!), and then an identifier with the field name.

Note that projections are special in that they may also appear to the left of a regular assignments, e.g.,

test.value1 := 84;

may be used to update the values of fields in instances.

Next

This defines the basic statements and expressions in BraneScript, and can already be used to write simple programs. Refer to the user guide to find more information about how to do so.

This documentation continues by going in-depth on some other parts of the language. In particular, subsequent chapters will deal with the formal grammar of the language; scoping rules; typing rules; workflow analysis; and other compilation steps. The final chapter in this series concludes with future work planned for BraneScript.

If you're no longer interested in BraneScript, you can alternatively read another topic in the sidebar on the left.